India needs robust Industrial Policies

And no, it cannot be tariffs or protectionism. Although Production-Linked Incentives could be one of the tools.

I

Industrial Policy (IP) is notoriously tricky to define. I’ll use the most common definition — IP is any policy that aims to transform the structure of the economy. That could be transforming an agrarian nation into a manufacturing one. In India’s case, while agriculture contributes around 18% of the GDP, it employs almost half the workforce. A well designed industrial policy could support labor intensive industries that move the workforce into manufacturing. Not having an IP is equivalent to having an IP for the current structure of the economy.

Even developed countries could use such policies. The US is infamous for regulations restricting land use, zoning and building. New York City couldn’t be built today the way it once was—40% of its buildings wouldn’t meet current codes. And when you want to promote industries on the technological frontier — batteries, solar, drones, autonomous driving — there’s a lot to learn from Industrial Policy. I’ll give three examples:

Ronald Reagan — known for trickle-down economics and free markets — famously said “Government is not the solution to the problem, government is the problem”. But even he protected domestic steel and auto industries to encourage them to invest in technological upgrading1.

President Pinochet of Chile was the posterboy for free markets2. Even he promoted the forestry sector with immense subsidies. Unfortunately, the deleterious impacts of these policies on the environment are still being felt3.

Margaret Thatcher, the British PM, was responsible for extending favorable terms to Nissan and getting it to open up their manufacturing shop in the UK. Honda and Toyota soon followed in the 1990s.

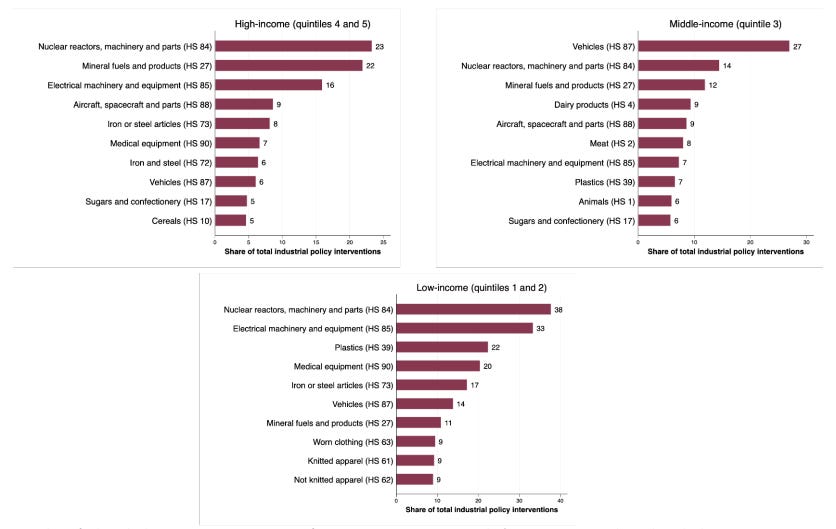

The above chart shows the sectors that countries in different income levels promote using IP. (Juhasz, 2023)

IP covers a large spectrum of policies. The most obvious are tariffs on imports and import quotas. They’re broad tools and usually end up hurting consumer interests. There are production subsidies like India’s Production-Linked Incentives (PLIs). Many countries set up Special Economic Zones (SEZs) where there’s a lot less regulation. China famously employed these SEZs in the Southern part of the country for industrialization with Shenzhen being the most famous.

There are objections to IP, but they’re often based on empirical concerns rather than first principles. The biggest objection is often some version of “governments cannot pick winners”. And there are always partisans choosing their favorite successes or failures to make their point. There are successful examples of IP like:

The East Asian Tigers’4 success is often attributed to correctly designed industrial policy.

China is often the flag bearer of industrial policy. Its SEZs, protectionism, state funding and export subsidies have vaulted it to the pole position in a number of frontier technologies, some of which include batteries, language models and autonomous cars.

Malaysia’s success in building a semiconductor industry successfully.

Brazil’s modest success in erecting a world class aircraft manufacturing industry.

Joe Biden’s CHIPS Act was successful in getting TSMC to build a manufacturing plant in Arizona and it recently started producing chips.

However, free market purists will point to other failures of industrial policy like:

The Concorde was the fastest airplane to hit the skies, covering the distance between London and New York in 3 hours. What started off as a joint venture between Britain and France, ultimately failed in making the airline commercially successful and it ended up being scrapped.

India’s many industrial weaknesses are a perennial source of failures despite successive governments encouraging industries5.

Malaysia had a flagship state enterprise to manufacture cars known as Proton. Malaysia attempted to establish an internationally competitive car sector through the enterprise but was ultimately unsuccessful.

The US government provided Solyndra — a solar panel manufacturer — with over $500 million in loans to promote solar and create jobs. Unfortunately, the company ended up declaring bankruptcy.

To ensure I am not attacking a strawman, I’ll include the strongest critique of industrial policy from the Hoover Institution:

There are two problems with industrial policy: information and incentives. Government officials don’t have, and can’t have, the information they need to carry out an industrial policy that creates benefits that exceed costs. Also, they don’t have the right incentives. If they spend literally billions of dollars of government revenue on buttressing an industry and the industry fails, they don’t suffer any personal wealth loss and don’t even lose their jobs. The only cost to them as individuals is their prorated share of tax revenues, which will typically be no more than a few hundred dollars. So what ends up happening is that subsidies and preferential treatment are given to the politically powerful, which reduces the amount of capital available for unsubsidized entrepreneurs and innovators.

And to be clear, this is a fair critique of IP. Taxpayer dollars are valuable and they must be put to good use rather than frittered away.

But as Juhasz, et al argue in their recent paper, “The New Economics of Industrial Policy”:

But ultimately what is required for industrial policy to work is far less than a consistent ability to pick “winners.” In the presence of uncertainty, both about the effectiveness of policies and the location/magnitude of externalities, the ultimate test is not whether governments can pick “winners,” but whether they have (or can develop) the ability to let “losers” go. As with any portfolio decision, it would be an indication of sub-optimal policy if the government did not back some ventures that end up as failures ex post.

In the U.S., Department of Energy loan guarantees to Solyndra, a solar cell manufacturer, failed miserably; but a similar loan guarantee to Tesla enabled the company to avert failure and become the behemoth it is today. In Chile, successes in four projects supported by Fundacion Chile – including most spectacularly salmon – is said to have paid the costs of all other ventures.

Letting losers go may still be a hard task, in light of political pressures that inevitably develop. Indeed, Solyndra, for example, was backed by the government long after it became clear that the company would not become financially viable. But it is far less demanding than governmental omniscience. Ensuring that governments can stop backing evident losers requires a set of institutional safeguards that include clear benchmarks, close monitoring and explicit mechanisms for reversing course. [emphasis mine]

In this day and age, with frontier technologies requiring massive capital and tight coordination between multiple industries, IP is required to solve any coordination failures. For example, an indigenous semiconductor industry may never develop because it wouldn’t be cost competitive initially. But if the initial learning could be subsidized, it may pay off in the future.

II

For Indians, Industrial Policy (IP) conjures images of the pre-1991 era with tariffs, import quotas, import substitution and the license-raj. With economic liberalization unleashed in 1991, India saw immense growth with economic strictures falling away. Since then, there’s been a consensus among a wide section of the Indian intelligentsia that the government’s involvement in industry6 caused the economy to stagnate. IP needs to be viewed through a different lens.

As I elaborated above, as long as the policy design allows the government to let losers go and the government actually follows through, IP stands to benefit broader society. There are tons of benefits for India to have its own IP — I’ll list out three:

Any advanced technology requires tons of Research and Development (R&D). For any firm doing such R&D, there are technology spillovers into adjacent areas. For example, because of NASA’s moon mission, the world was able to get the benefit of freeze-dried food, aerodynamic swimsuits, memory foam, building shock absorbers and many more. These are global spillovers of R&D. The Internet itself wouldn’t exist without DARPA’s funding. India is the world’s largest arms importer and spends precious foreign exchange doing so. Funding an IP in defence would lead to saving aforementioned forex and help in exporting arms to other countries7.

Coordination failures in moving to greener, sustainable technologies hamper adoption. For instance, solar has tremendous upsides but the initial cost of installation puts off many consumers. Solar panel manufacturers can never get the economies of scale needed to reduce costs. Government subsidies to manufacturers and consumers — a form of IP — can help out here.

Some parts of India are backwards due to various socio-economic reasons8. Setting up industry there would provide a much needed source of jobs. Since industry benefits from clustering effects, being the first company to set up shop in such areas would face problems in recruiting talent — among others. IP is a great tool to use to subsidize such costs.

India was forcibly deindustrialized through colonization and the initial decades since independence bear that out. Agriculture contributed to half the GDP and employed three quarters of the workforce. While agriculture’s contribution to GDP has come down over the decades, there’s still half the workforce remaining in agriculture.

Services have been contributing most to GDP in recent decades, accelerating since the 1991 reforms. Services can’t be mass employers unfortunately. Even body shops like the Indian IT services can’t employ as many people as a textile company can.

Sadly, manufacturing hasn’t been able to improve its contribution to gdp. Modi’s aim is to increase manufacturing’s contribution to Gross Value Added (GVA)9 to 25%. So far it hasn’t borne out. There are various reasons for this, ranging from labour laws to difficulties in getting access to factor inputs10.

Successful industrial policies11 for India must reshape both employment patterns and the broader economic structure. Approximately 12 million people join the labour force every year. Ideally, a few million would be moved away from agriculture and into more productive manufacturing or service jobs every year. The Labor Force participation Rate (LFPR) for India stands at about 58% compared to almost 75% for the US. Bringing that up to developed world standards would involve creating a few million additional jobs a year. That means India is looking at the formidable challenge of generating about 16 million jobs a year.

III

If you’ve read this far, hopefully I’ve convinced you of the need for an aggressive industrial policy.

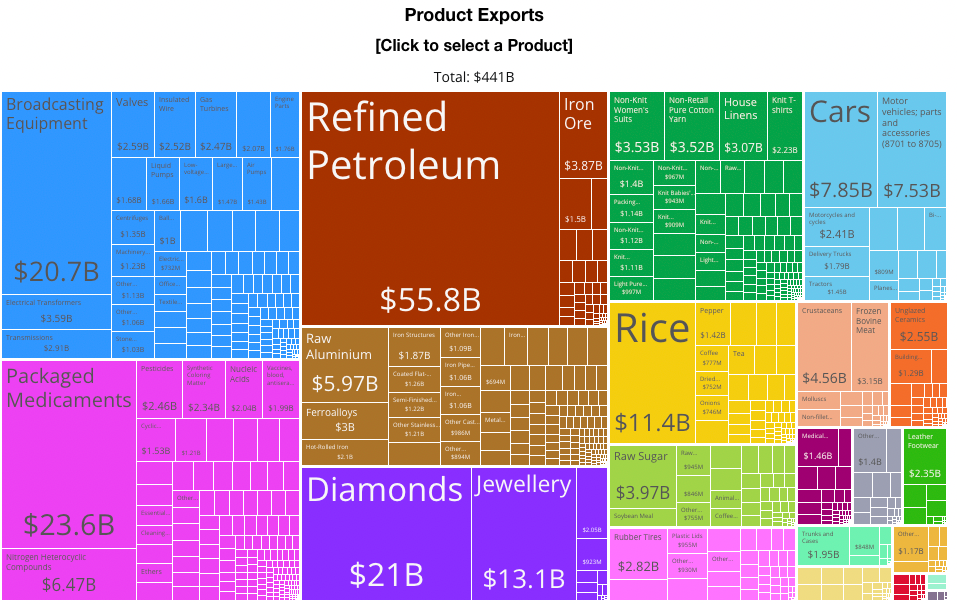

Contrary to public opinion, Nehru’s socialist model with its focus on heavy industries wasn’t really as big a failure as imagined publicly12. Using SITC13 data, Felipe, Kumar and Abdon (2010) show that for a country at its stage of development, India has a highly sophisticated export basket. Despite India’s comparative advantage being labor intensive products, it has done very well in capital and skill intensive markets. The Nehru-Mahalanobis model of development invested in capital heavy industries with moderately successful outcomes.

I’ve (not so) subtly blamed tariffs and other protectionist measures throughout this post. But that’s not the whole story. China is famous for its heavy protectionism. Yet, it still managed to join the ranks of upper middle income economies. America has a long history with protectionism too. Britain aggressively pursued protectionist measures in the late 19th and early 20th century. There are other examples of the developed West dabbling with protectionism. If protectionism was undesirable and free trade was the be-all and end-all, these countries wouldn’t have developed. Free trade provides an impetus to development, but even without it, countries can develop with good policies. The free trade consensus of the early 1990s and 2000s was seen as hollowing out America, leading to the rise of Trump’s terrible tariff regime. So what other policy held India back?

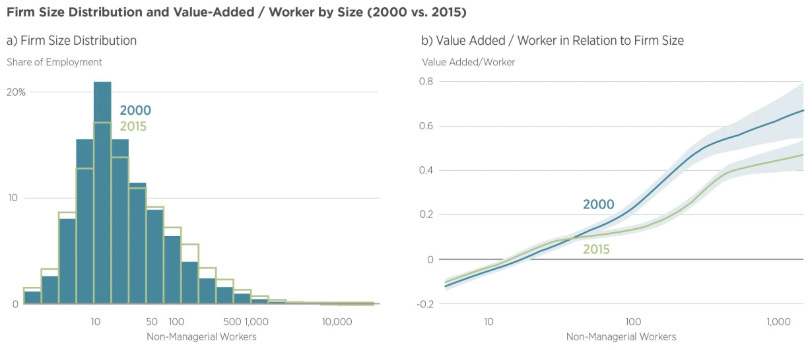

The answer to this: The Small-Scale Reservation Policy (SSRP). Under this policy, certain items were reserved to be manufactured exclusively by the small scale industry. How did the government define small scale? By the amount of capital a firm had invested. The limit was Rs 1 crore in 2015 (about US$150,000) and has now been revised to be Rs 10 crore. By 2002, there were around 800 items reserved exclusively for this sector. Over the next decade, they would slowly be whittled down, until in 2015, the last 20 remaining items were dereserved as well.

The downsides of this policy were immense. Any firm specializing in these items couldn’t organically grow otherwise it would be disbarred from producing them. Large firms couldn’t leverage economies of scale to produce the items at a lower cost. Small firms were prevented from naturally expanding into other areas because they couldn’t compete with larger companies on non-reserved items.

Depending on the method of measure, if India hadn’t adopted such a policy, its manufacturing sector would have seen an aggregate increase in Total Factor Productivity (TFP) of 40-60%14 between 1987 - 1994. To put this into perspective, if capital and labor in the economy remained constant and everyone’s productivity grew by 50%, the GDP itself would grow by 50%. With capital and labor entering the Indian economy during that period, the growth would have been even faster and India might have joined the ranks of upper middle income economies by now.

IV

So what does successful IP look like for India? What are some concrete policy suggestions and what roadblocks need to be removed?

Free the Labor

Labor laws are the metaphorical thorn in the foot for the country’s enterprises. Any company above 300 employees requires permission from the government for retrenching its workforce. It shows up as 92% of firms in the country having less than 100 employees15. This statistic also implies that firms probably employ more labor on a contractual basis. Sen, Saha and Maiti provide evidence in support of that. I covered labor laws in more detail in a previous post.

India has a Revealed Comparative Advantage (RCA) in labor intensive sectors. Comparative advantage is the principle that a country (or person) should specialize in producing the goods or services it can produce at a lower opportunity cost than others. Even if one party is more efficient at everything, both sides can still benefit from trade by focusing on what they give up the least to produce. RCA is a metric that shows whether a country is relatively better at exporting a particular good compared to the world average, offering a practical way to observe comparative advantage through trade patterns.

Exploiting this RCA is important to generate the 16 million jobs that we calculated earlier.

Policy Coordination

There’s a tendency to view IP as a single policy. In reality, it is a bunch of policies closely tied together that offer some concrete benefits. While subsidies and export support are common tools, there are other policies that need to be worked on.

For example, to export more textiles, India needs more ports and highways to reach those ports from manufacturing regions. Similarly, getting better at state of the art semiconductor manufacturing requires clean air and water. Even a speck of dirt in a manufacturing facility can cause an entire batch of wafers to be thrown away. These aren’t traditionally thought of as IP, but some industries can’t exist without it.

Many Indian states have electricity utilities managed by the state government. Often used to grant favors to key constituents by politicians, they run into massive losses. Industry is the first to suffer because they have minimal votes. Without electricity generation, the best IP won’t be able to attract companies. And even if it does, it won’t be able to keep them.

The DARPA Model

The US has had tons of R&D spillover from DARPA. The Defence Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) sets up problem statements in frontier technologies, invites companies to apply and then funds the most promising applications. The list of its impact is long and includes the Internet among others. GPS was a DARPA project too! There are many failures here, but the successes have been spectacular. If there wasn’t DARPA, there might not have been a Google Maps.

The learning here applies to India. With the Army importing a large amount of arms, not only is this needed to reduce imports and save foreign exchange, it is an absolute imperative for national security.

There have been positive steps taken by the government in this regard and Big Bang Boom Solutions has been one of the success stories. These policies need to be stepped by an order of magnitude.

Embedded Autonomy and learnings from Peruvian Mesas

Often, there’s been (well-meaning) suggestions that industry and government should have a barrier to prevent stigmatized and crony capitalism from taking hold. It is well intentioned, but ultimately this approach is doomed to failure.

The state is often sufficiently independent to act purposefully but without input from broader society, it cannot gain necessary information sitting in its ivory tower16. To have the best chance of success, an IP should adopt the structure of Embedded Autonomy. Put forward by Peter Evans, it argues that any successful state intervention has two components:

Autonomy, where the state is empowered to act in its long term interests without undue influence from pressure groups.

Embeddedness, where it establishes dense, concrete connections with elites and entrepreneurs through which it accesses critical information and develops a forward thinking entrepreneurial class.

This idea is bold and very ambitious for Indian society which is riveted with divisions — primarily caste and religion. But walling off the state from society will lead to ineffective interventions. Without such embeddedness, the flow of information between bureaucrats and firms stops. That’s disastrous because there’s often informational asymmetry in this relationship.

A good working example of an upper middle income country that practiced this with good success comes from Peru. Peru established mesas that put this concept in practice. It is a good example of building durable industrial policies in lower-capacity environments.

Special Economic Zones (SEZs)

SEZs are a common policy suggestion so I won’t spend a lot of time on it. Essentially the government sets up a geographic area where the trade and business laws are different from the rest of the country. They’re effective when business friendly reforms are politically impossible in the entire country, so the government creates a smaller area where business is easier. GIFT in Ahmedabad, Gujarat is a recent example of such a SEZ. To be really effective, there must be only a few such zones and they must be big to allow clustering of firms to occur.

India has about 300 such zones. That’s ineffective. China has fewer zones and people know the most famous by name — Shenzhen. And here, India doesn’t even have to do anything innovative. Simply copy China’s playbook modified to Indian environments.

Free Trade

As Trump has shown with his tariffs, free trade is extremely important. While protectionism isn’t the death knell to development, it makes it harder. Tariffs are a blunt tool for protectionism. They don’t have automatic sunset measures. Once put in, they’re extremely hard to remove. A political lobby forms around the tariffs and pushback against reduction is extreme. This is evidenced from the US steel sector.

Importantly, no country on the face of the Earth is self-sufficient in everything. Intermediate inputs are required for all industries and tariffs make them expensive. Counterintuitively, they make the end products more expensive for the domestic consumer. That consumer doesn’t have a choice, but the industry will be uncompetitive internationally with its higher prices. It would be unable to expand into international markets.

India still has relatively high tariffs. That makes the cost of its end products more expensive to users. The free trade regime that started in the 90s did more to improve consumer welfare in 10 years than the tariff based regime did in the 40 years since independence.

There is ample evidence that trade liberalization and specialization gradually moved India from low-tech sectors to more complex ones. Industries that faced the largest tariff reductions have seen the largest improvements in trade specialization. Individual firms might be hurt, but the overall sector prospers.

Production-Linked Incentives (PLI)

PLIs offered subsidies for hitting production targets for participating companies. Applicable to 13 sectors — textiles, semiconductors, batteries and solar among them — it aimed to boost production and knowhow in these technologies.

The one crucial element it lacked was an export subsidy. However, the goal wasn’t for the companies to export, but to expand nationally and increase production. It was wildly successful in getting the semiconductor industry into India.

In other sectors though, it achieved limited success before being withdrawn. Mainly, it involved multiple agencies coordinating along with turf wars. Pranay Kotasthane has a good writeup on the topic so I won’t repeat the analysis.

As an industrial policy, I loved the PLI scheme, but until underlying factor markets are improved, such schemes will continue to have limited success.

V

There’s a whole bunch of reasons to be optimistic about Indian manufacturing and its exports. India’s exports (shown below) have high economic complexity compared to its per capita income. However, it can improve even more by adopting targeting industrial policies.

The biggest problem India faces right now is dualism. An informal sector employs the majority of the workers, but is low on productivity whereas the formal has high productivity but employs less workers. This drags down the TFP of the economy, reducing growth. Workers aren’t part of the tax net and subsequently lose out on welfare schemes. Firms don’t get benefits of formalization and are forced to remain small.

With good IP, these problems can be resolved and TFP growth can really accelerate. Growing TFP is the most essential since it measures the efficiency of resource usage to produce an output. GDP can grow by applying more inputs of labor, land and capital. The more land you throw at agriculture, the more will be the output. But after some time, you run out of land. That’s when how land is used matters. Long term, only TFP growth will allow India to join the ranks of developed nations.

Whether it bore fruit is an entirely different topic of discussion.

Chile’s experience with free markets is fascinating. President Pinochet was the military dictator of Chile. He introduced free market reforms which led to favorable developments in all Human Development Index (HDI) indicators. In 1990, power was transferred peacefully from President Pinochet to a democratically elected government. Milton Friedman famously said, "Chilean economy did very well, but more importantly, in the end the central government, the military junta, was replaced by a democratic society. So the really important thing about the Chilean business is that free markets did work their way in bringing about a free society."

The failure of an industrial policy shouldn’t be equated with failures of industrial policy in general. It is hard to design good industrial policies and countries need to learn from experiences of others.

Usually considered to be Hong Kong, Singapore, South Korea and Taiwan.

We’ll see later in the post that India actually did pretty well with industrialization for its income levels and the main factor that hamstrung it was often onerous regulations.

The Nehru-Mahalanobis socialistic approach of industrializing.

This is already starting to happen. Small scale defence manufacturers have gotten initial orders from the Indian military and they are even being helped to export arms to some African nations.

Think Bihar, Jharkhand and the northeastern states.

GDP measures the total value of all products produced in the economy. GVA measures the total value added by products after deducting intermediate inputs. So if components were imported and assembled in India, adding only a tiny bit of value, the GDP would look good if the component was an iPhone, but the GVA would be insignificant in comparison.

Land, labour and capital.

Note the plural. India needs multiple industrial policies, not a one-size fits all.

To be clear though, it was a failure. While it did help set up heavy industries in a socialist model, import substitution, quotas and tariffs protected industry from competition and harmed consumer welfare. Also, without commensurate investment in infrastructure, there’s a limit to how much Industrial Policy can pay dividends.

Standard International Classification of Trade.

The authors do the calculation for both China and India. They basically measure what the TFP for both the countries would have been if their productivity had been the same as their US counterparts.

Until the new labor laws were passed, the threshold where various government regulations kicked in was 100 instead of 30o, which is why there’s so much clustering below the 100 employee mark.

A charge often levied at the Indian bureaucracy.

I agree with much of this while continuing to believe Industrial Policy is fraught with issues. I feel that the title is more provocative than the proposal. Much of what you are proposing is sound-headed factor reforms, as opposed to 'Industrial Policy'.

My definition of IP is government trying to forecast the key industries of the future, pick the winning sectors, and invest heavily with subsidies in those sectors & even specific firms. Labour reforms, policy coordination, and free trade are all general-purpose reforms that I very much support. R&D investment, I believe, is a part of innovation policy and I very much agree with what you are proposing if govt funds a broad spectrum of research in universities & private industries (see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4gqPR0veij0).

The two things that would qualify my definition of IP are PLIs and SEZs. Both exist in the Indian context, which means that India already _has_ an industrial policy, and it has hardly worked so far. I still have some hope from SEZs if they are done in a more decentralised manner (so much so that, at some point in 2022, I left my job to join 'Foundation for Economic Growth' which aims to help govt do this well - a story for another day!). See Yuen Yuen Ang's book on China escaping the poverty trap. It was a highly decentralised affair. The central government gave a broad mandate to raise private investment, and local governments went all out.

I think in the level of importance/impact, PLIs come last among these. I don't have very strong feelings about it. I have a slight non-preference for them given our poor state capability, but I'm fine with some trial and error. But these trial & errors make sense when there's action on the other 4 things also - in isolation, they can't do much. PLIs in India are currently a compensation/refund for the inflated cost of doing business. How about going to the root cause and fixing the indirect taxes? I know that's a long road and I'm ok with PLIs as an interim measure as long as there's some progress on other factor reforms.

You've hit the nail with SSRP. Note that this was also a particular kind of industrial policy (a bad one, yes). Which brings me to my larger point - I would argue that it shows that it wasn’t a lack of good Industrial Policy per se that held India back; rather, it was an active shackling of the markets. It was this belief that we can forecast what's and act on creating better outcomes for the poor in the economy (which is strangely the assumption in doing good IP also). So I think unshackling will pay a high dividend: land, labour, fixing the indirect tax mess, etc.

I also don't agree that “not having an IP is equivalent to having an IP for the current structure of the economy.” This doesn’t seem correct to me. Markets do change the structure of the economy when allowed to operate (even without IP).

As a side note, check out Rajan & Lamba's book "Breaking the Mould", where they argue that India should double down on services. I don't have a view, but plugging a review I had done for the book: https://open.substack.com/pub/fahadhasin/p/rethinking-indias-growth-path. Also, Ajay Shah & Amit Varma's recent ep on Industrial Policy: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lP1GIFO5ED8

Thanks for writing this much-needed piece. I hope it reaches the right people, like how your earlier piece may have influenced Surjit Bhalla :)

Industrial policy often receives disproportionate attention in the media and policy discussions, even among those who acknowledge its necessity. This focus can be misleading, as it often overshadows more fundamental issues that require urgent attention.

It is unsurprising that Indian politicians are more interested in impressing foreigners and Non-Resident Indians (NRIs) than addressing the core problems of their own country. Instead of chasing the latest trends in industrial policy, India should prioritize creating an efficient and predictable legal system. This involves ensuring law and order by investing in law enforcement and devolving power to local cities. Additionally, liberalizing the electricity and agriculture sectors is crucial for fostering growth and development.

India must avoid getting sidetracked by Western fads and concentrate on solutions that offer the most significant impact. While hiring more judges or addressing teacher absenteeism in schools may not be as glamorous as discussing industrial policy with American friends, these are the initiatives that truly matter for the country's progress. A nation that cannot maintain the rule of law and simplify its tax system has little hope of success, regardless of the relevance of industrial policy.

The sophistication of India's export basket is more a testament to the pathologies of its policymakers than to any success in industrial policy. If India had enabled low-skill manufacturing and agriculture to flourish, it would have achieved much greater success. A case in point is Bangladesh, my home country, where despite a more incompetent and despotic political class, per capita income is comparable to India's, even though Bangladesh started from a lower base and has a lower average IQ.

By focusing on the fundamentals—rule of law, efficient governance, and strategic liberalization—India can build a stronger foundation for sustainable growth and development.