Indian Agriculture #4: Doubling Farmers' Income

Increasing the income of the most vulnerable class

This is part 4 in a series on Indian Agriculture. Part 1 dealt with how socialism has ruined Indian agriculture.

Part 2 talked about price controls and their corrosive effects on agriculture and other parts of the economy.

There’s a bonus part 2.5 where I refute the arguments of a farmer activist who penned a column in The Indian Express.

Part 3 deals with the infamous farm laws and why they were necessary to liberalise agriculture.

Let’s get one thing out of the way before we start. In one sense, the title of this post is clickbait, just like the political promise made by Prime Minister Modi1. Why do I say so? The short, one word answer is inflation.

Depending on which source you consult, the average inflation for the past 10 years in India has been between 5-6%. Nominal income2 that grows at this rate will take about 12 years to double3. Naturally, we are interested in real income, that is growth in income after inflation is taken into account. Neglecting real income, farmers’ income have close to doubled in the preceding 10 years.

Farmers’ nominal incomes grew from Rs. 6,426 in 2012-13 to Rs 10,218 in 2018-19, a nominal growth of 59%.4 Inflation was about 36%5 during the same time period. Unfortunately, this implies that real income grew 23% only during the same period. That is a yearly growth rate of about 3.5%,6 while the wider economy grew at an average rate of 7.5%.

This widening inequality is worrying for a number of socio-political reasons. Unless agricultural issues are resolved, India can’t get to a upper middle income economy. So what are some methods to double farmers’ real incomes?

I’ll go through some recommendations for improving farmers’ incomes based on the principles of free markets, and the recommendations of the Ashok Dalwai committee7.

Organic Farming doesn’t improve incomes

The government has started a few programmes to promote organic farming, to assist farmers starting out in the business. India also has a certification agency, National Programme for Organic Production (NPOP) that lays out standards for organic produce. At present, around 4% of the country’s total sown area is being used for organic farming8, and this is only going to grow.

A fundamental misunderstanding often pervading these discussions is that organic farming is considered to be a premium good, sustainable and healthier than conventional produce. As a result, governments around the world (India being no exception) have been spending money to either promote or subsidise it. Even the Ashok Dalwai report that I mentioned above promotes organic farming, although to their credit, they do nuance it with multiple caveats. Why can’t organic farming be a solution to increasing income? Primarily because:

While organic farming fetches higher prices at the market, the inputs involved are much more expensive as well.

Yields are much lower in organic farming. There’s approximately a 18-20% drop in yields. The same amount of land is producing less. So while organic produce does fetch higher prices at the market, the overall difference to the farmer’s pocket is likely minimal.

Much importantly, at an aggregate level, because organic farming yields less produce per hectare, producing the same amount of output would convert much more land in the country into agricultural land. That is a situation the country can’t afford. Farmers can afford it even less. Land acquisition for other projects would become even more of a problem.

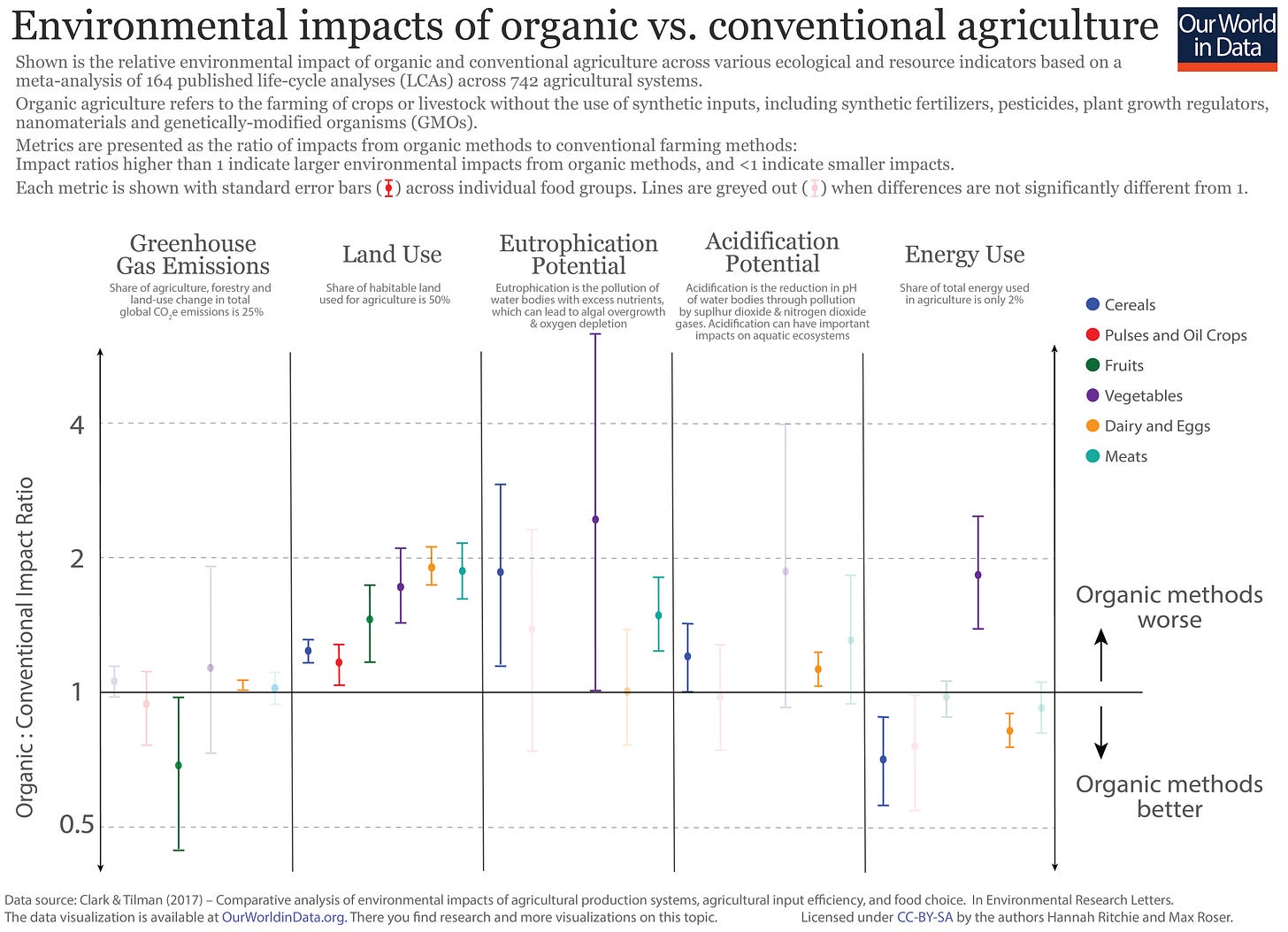

Higher land use in agriculture requires deforestation, release greenhouse gases and has a number of adverse environmental effects9. Ideally these effects would be limited to small sections of land if agriculture is practised conventionally rather than organically. Also, with farmers already struggling with incomes, how are they going to find the money to buy more land?

A convenient chart by Our World In Data lays out the environmental choices faced when comparing organic vs conventional farming.

Genetic engineering has great potential

Genetically engineering (GE) crops are those that have had genes inserted, modified or removed using recombinant DNA technology. I find the term 'genetically modified' misleading, as every food item from farm to table has experienced some degree of genetic modification. Preserving seeds only from the plants that thrived on the farm is, in itself, a form of genetic modification, as it applies artificial evolutionary pressure to the crops. While the US is the world’s largest producer of genetic crops, the only legal GE crop in India is Bt. Cotton. There are around 20 other crops in various stages of research and field trial in India.

There’s a lot of resistance to the idea of genetically engineered crops. Part of that is mistrust with the corporate ecosystem itself. I’ll ignore those criticisms for now, because corporate and legal structures are continuously evolving and conditions unfavorable to farmers and consumers change. I want to briefly address the concerns surrounding the consumption of the crops themselves.

Are GE crops safe?

There is enough research at this point to answer this question with a resounding yes. The FDA (Federal Drug Administration) and the USDA (US Department of Agriculture) have both said that there are no adverse effects on humans. Further, there are no adverse nutritional effects of such crops and they are completely identical in nutritional value to those grown conventionally.10

Do GE crops adversely affect the environment?

A resounding no. Counterintuitively, GE crops can sometimes be safer for the environment. Many GE crops are designed to produce a specific protein or gene that targets harmful pests while remaining harmless to humans. This reduces the need for chemical insecticides, leading to less pesticide runoff into nearby rivers, lakes, and oceans—a clear win for the environment!

This causes less economic loss for farmers, both via increased yields and less input usage. The productivity of land automatically increases and with that, farmers’ incomes.

Could genetic material transfer itself from the crop to humans?

Another concern is that the modified gene could crossover to humans during digestion. While likely, the chance that it causes any harm is minuscule. The absolute quantities of edited genes consumed isn’t high enough on its own to cause harm. Remember, the dose makes the poison.11

It must also be remembered that GE crops don’t exist in a vacuum. You have to consume something. If not GE crops, then it will be conventional crops. And who says that conventional crops aren’t genetically modified? Selective breeding methods alter the genetic makeup of crops. With genetic engineering, there is precise control over which gene exactly gets altered. So isn’t that much better than random mutation?12

I don’t want to make an already long article longer so I won’t address other concerns. There are multiple sources linked throughout that explore the safety and health issues involving GE crops.

With that out of the way, what is in it for Indian farmers to adopt GE crops? How does it raise their incomes?

GE crops usually end up improving yields. The crops themselves aren’t engineered to have higher yields, but are often engineered to be resistant to certain pests. This also necessitates less use of insecticide. There’s a bonus here. There is greater yield with less use of pesticide, which leads to improved incomes.

There are methods to engineer crops to make them drought resistant, which automatically makes them use less water. Such varieties of rice, sorghum and cotton are being researched in India. Using less water is unquestionably good for the environment. Additionally, because areas of Punjab are facing receding water tables, this helps Punjab farmers reduce the electricity used to pump the water out.

With enough interest, farmers can tie up with laboratories to develop custom genetic crops for specific industrial requirements. This is premium industry and if it takes off, can really improve farmers’ economic situations.13

Implementing Bhu-Aadhar on a war footing

One of the (rare?) policy successes in the Indian governance landscape has been the implementation of Unique Land Parcel Identification Number (ULPIN), commonly called Bhu-Aadhar.

Bhu-Aadhar assigns a unique ID to each land parcel. This provides enhanced transparency, fraud detection, easier loan processing for banks, easier implementation of government schemes and reduction in boundary disputes. The Central government is pushing for completion of this exercise by 2026, but it seems a tall order since only 30% of rural land parcels have had this exercise completed.

How does this benefit farmers economically? About half the civil disputes in the country are related to land. Implementing this on a war footing reduces the profitability of civil disputes, saving farmers’ expenditure on civil cases.

As discussed earlier, land fragmentation is a major issue hampering productivity. Various land pooling measures could be instituted better if Bhu-Aadhar were completed faster. For instance, a Farmer Producer Organisation (FPO) could be instituted by a group of farmers, coming together to pool their land. This would not only allow economies of scale, but also allow better negotiating power with traders.

At present, farmers often end up losing out in land transactions due to the opaqueness of the transaction. ULPIN would help develop a transparent land market that creates a safety net for farmers wanting to dispose of land.

Inserting Technology in Agriculture

This is going to be a catch all section for improvement of economic outcomes using technology. The overarching theme of this section is creating transparency across the entire supply chain.

Drones are increasingly becoming cheap14, and can be used for aerial monitoring of various aspects of the farm. Drones can spray pesticides, monitor crop health, measure nitrogen content of crops among other things. If implemented alongside land pooling, it can be transformative by reducing dependence on labor.

Increasing the use of robotics in agriculture is also a worthy endeavor. If sensors are planted across the field, the precision of interventions increases dramatically. Robotics also automates tasks replete with drudgery, and can provide consistent quality of labor. Sensors can detect weeds and pests among crops, reducing indiscriminate usage of herbicides and pesticides. This would have the side effect of reducing pesticide, and could compete with organic produce on the pesticide residue metric.

When grains are stored, sensors in storage houses could continuously monitor storage conditions and alert when conditions are suboptimal. This would reduce spoilage, increasing yields further.

With increased monitoring, insures are better able to assess risk. Judging risk better allows insurers to offer competitive rates and also nudge farmers towards the right technologies. For example, there could be insurance discounts for farms installing sensors. Better risk management also allows the PMFBY (Pradhan Mantri Fasal Bima Yojana) to increase the amount of crop it insures for the same amount.

All of these are small measures on their own, but combined have the potential to transform agriculture. Each existing government intervention that is removed, brings farmers closer to the existing market and consequently closer to prosperity.

In my mind, the farmer laws that the Modi government was forced to repeal were as close to an ideal reform as could be possible. It got rid of the farmer-saviour complex that has beset the Indian state since its inception with one stroke of the pen. Unfortunately, it is likely that the current government wouldn’t have the political appetite to bring back those reforms15.

Absent those, I’ve attempted to outline reforms and policy decisions that require minimal political capital from any government or leader. Astute readers will notice that there’s a pattern to my recommendations. The default position I assume is to nudge the policy consensus towards free market principles. Adam Smith’s invisible hand often produces the most optimal outcome with everybody working in their own self-interest.

Technically Arun Jaitley was the one who made the promise, but he couldn’t have without Modi’s backing.

Nominal income is the actual value of income that you earn. Real income takes inflation into account. For example, if income grows at the pace of inflation, then the nominal income is growing, but real income is stagnant because purchasing power doesn’t increase.

You can quickly calculate this using the Rule of 72.

The source for this is the government’s press release on Press Information Bureau.

I have used a quick calculator online that aggregates data from World Bank. Depending on what data source you use, your results might vary but ideally should be within the same vicinity as mine.

The Modi government constituted a committee led by Ashok Dalwai in February 2016. The committee submitted an extensive 14 volume report that runs into thousands of pages. The complete report is worth a read.

The total area under cultivation is around 130 million hectares while the area under cultivation certified by NPOP as organic is around 5 million hectares.

And yes, this is true of organic farming as well. Organic farming impacts the environment differently than conventional farming, but on the whole it ends up being a wash.

Interestingly, GE crops can actually be engineered to have more nutrition than their conventional counterparts. Golden Rice has been engineered to have Vitamin A, a feature that is useful in Sub-Saharan Africa where children often lose eyesight due to lack of Vitamin A. GE crops can literally save the world!

I always like to say that in the right doses, even water can be considered a poison. Consuming enough water over a short enough of duration of time, can cause hyponatremia which can be fatal. This is actually a risk in high endurance events like marathons, triathlons and ultra-marathons.

Please don’t fall into the naturalistic fallacy trap!

They are becoming so cheap that the US army is considering using them in wars.

The other way to bring in these reforms is piecemeal by cajoling states to reform their agricultural laws. Since agriculture is primarily a state subject, states have the ambit for these reforms. But this is a big ask since there are some states (like West Bengal) that are permanently hostile to the Centre, especially if it is a BJP government.