Indian Agriculture #2: Why are price controls bad?

Offering a Minimum Support Price (MSP) for certain crops has skewed agriculture

This is part 2 of a series on Agriculture. I’ll update all the posts with links when I finish the series. You can find part 1 here.

Part 1: Indian Agriculture: Perils of Socialism

India is one of the world’s largest agricultural producers. India has the highest net cropped area in the world followed by the US and China. Major products are rice, wheat, milk and sugarcane among others. However, yields are very low across the board which is why even though India has the highest land under agricul…

In Punjab, soil health is deteriorating while it celebrates record paddy cultivation. Rather than leaving the land fallow for a cycle or using techniques like crop rotation, farmers are resorting to excessive use of chemical fertilizers. Crop diversity is on the decline. Villages are starting to run out of groundwater. Approximately 85% of the total area under kharif cultivation is used to plant paddy. Growing one kilogram of paddy requires around 3000 litres of water. With such serious problems, why do farmers insist on growing paddy in Punjab?

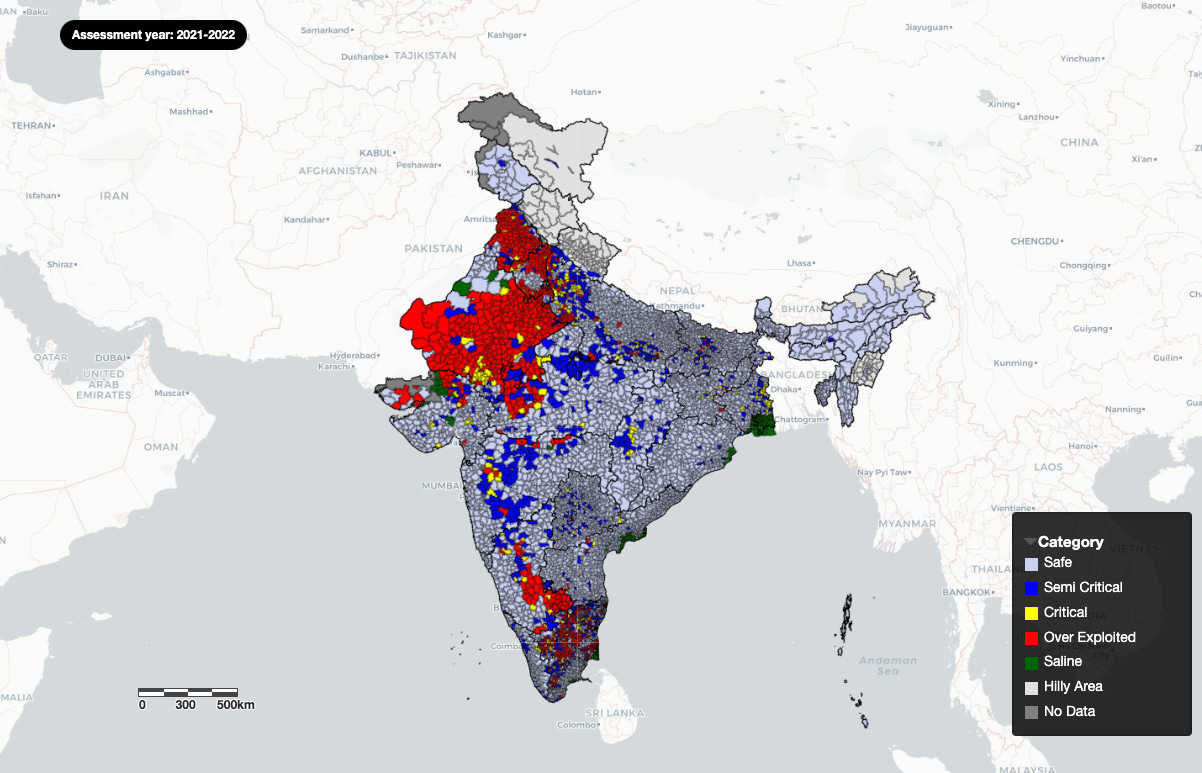

The image above shows the state of groundwater resources in India. Punjab has the highest share of groundwater resources that are overexploited. The state extracts more groundwater annually than what is naturally replenished. As a result, the water table depletes and the level of water every year sinks even further. The state is headed for dire times unless its pattern of agriculture changes.

Minimum Support Price (MSP)

Analysts put the blame on different factors like reluctance of farmers to test soil health, their reluctance to grow different crops and excessive dependence on chemical fertilizers. While true, I consider them to be secondary factors. The lion’s share of the blame should go the Minimum Support Price regime that the Centre supports1.

What is the MSP regime?

In 1965, the Agricultural Price Committee (APC) was setup. Its purpose was to advise on the price policy towards wheat, rice and 22 other crops, such that the price would incentivize farmers to invest in new technology that would increase yields. Setting up a price for procurement would ensure that the farmer wouldn’t face problems in case of a bumper yield. This was a major policy goal considering that at the time, India had yet to become self sufficient in food. This committee initially recommended setting up a MSP regime for certain crops. Every year, the APC sets the MSP for crops before sowing starts.

Simultaneously, the Food Corporation of India (FCI) was also set up. The FCI procures grains for its Public Distribution System (PDS) and also maintains a buffer stock of grains for food security. Out of the crops procured by the Government of India, wheat and rice account for around 40%.

Price Floors

Let’s take a brief detour to explore the concept of price floors. Price floors like MSP and minimum wage occur when the government intervenes in a particular market. If the floor is set below the market price for a product, then the price floor is ineffectual since producers will sell the good at the market price.

On the other hand, if a price floor is set above the market price, market distortion occurs. In the image above, S denotes the supply of goods and D denotes the demand for the same goods. As can be seen from the graph, when the price goes up, the supply for goods goes up, while demand correspondingly goes down. The point at which they intersect is the equilibrium price marked as E in the graph. At this price point, the producer can sell all the units they would like and the consumers can buy all the units they want.

If the price is artificially set higher, a deadweight loss2 occurs. Simply, because the price is artificially set higher, there is a surplus of produce at a higher price, but there is less demand because the price is high. It means that produce is in surplus. This distorts market signals leading to inefficient allocation of resources.3

Because there is a surplus in production a result of government mandated price floors, the excess supply will have to be bought by someone, which usually ends up being the government itself. Governments buy this with taxpayer money meaning some other program or scheme goes unfunded.

Finally, once put in place, price floors are extremely politically costly to remove. It’s because the benefits of removing them are diffused across the economy, but the cost is concentrated among a few constituents.

Distortions introduced by MSP

MSP introduces second order unintended effects into the market. At a large cost to the taxpayer, a few farmers in the Punjab belt benefit. I go through some of the more undesirable consequences below.

Unwanted surplus of MSP crops

The government announces a price floor for 22 major crops each year. Out of those, wheat and rice are grown the most since the government acquires stocks for its PDS and as part of its buffer stocks. Because of the price guarantee, farmers in Punjab grow exclusively wheat or rice. More than 80% of the area under cultivation during the kharif season is one of these two. The government has procured so much wheat and rice that it often rots in their storage. The image below shows the skew in procurement of wheat and rice compared to other crops.

Environmental Degradation

Consequently, the soil quality has nosedived, leading to excessive reliance on fertilizers. In turn, input costs rise, which again forces the government to raise the price floor. Water tables in Punjab are depleting alarmingly. The image at the top of the post shows how many overexploited groundwater resources are located in Punjab — natural ramifications of growing such water intensive crops.

Environmental effects are bad enough, the knock on economic effects are worse. MSP crops crowd out other crops that are essential for crop diversity and soil health. Worse, they lead to monocultures4 which render them particularly vulnerable to pests and disease.

Punjab and Haryana disproportionately benefit

The benefits of the MSP regime are concentrated in the Punjab-Haryana belt. Since most government procurement is wheat and rice, and farmers in that belt grow most of it, they benefit the most.

In a federal structure, it isn’t necessary that all schemes and programs must benefit all states equally. Having said that, this is unfair to other equally poor farmers in other parts of the country. Using taxpayers’ money for market distorting schemes is bad enough. Using it to favor one group of farmers over another is comically incompetent.

Only 15% of wheat procurement is from states other than Madhya Pradesh, Punjab and Haryana. How is this fair when there are farmers in Maharashtra committing suicides because of financial stress?

Cannibalizing the remaining agricultural sector

According to an SBI report, MSP crops account for only 6% of the agriculture economy, but if all MSP crops at MSP prices, it would cost Rs. 13.5 Trillion. To comprehend the magnitude of the figure, consider that India’s entire budget for the year is Rs. 49 Trillion. This is almost a third of the budget.

There is no question in my mind that the MSP regime needs to go for ecological, economic and equity reasons. Transitioning off of MSP will require spending political capital and having stopgap measures to ensure that affected farmers don’t lose incomes.

Various schemes exist that provide support to farmers without distorting markets. Strengthening and expanding them could be a way out of the current rut. The crucial question is: Can this government muster the political will to execute on it?

To be fair, there are some political compulsions that keep the support going. Nevertheless, someone needs to be willing to expend the political capital to end this regime.

The deadweight loss occurs due to units that aren’t traded, that could be traded if the price were lower. More consumers might be inclined to purchase the good if the price is lower. The government interferes with the free market and is now forced to pay for the surplus produce.

For instance, with MSP, farmers are incentivised to grow wheat and rice. The inputs consumed for wheat and rice are more than what would be consumed were there no MSP. The distortion can have other ripple effects in the economy that are hard to anticipate.

Monocultures are fields where a low variety of species of a particular crop is grown.

I didn't realise the fiscal burden of this system could be so large! Suppose that tells the same story that you mentioned - hard to get rid of when a small bunch of people are benefiting to such an extent and would fight tooth and nail against repealing it...

Yep! Costs are diffused and benefits are concentrated.