China uses trade to forcibly de-industrialize India

And a short note on the role of Reserve Bank of India (RBI) in Industrial Policy

An Appeal:

Before diving into this week’s post, I wanted to share a quick note. I’ve been writing on Substack for about five months now, with a simple goal: to explore ideas through an Indic lens rather than the default Western-centric frame. Think of it as a subaltern perspective—one that foregrounds India’s unique history, culture, and political economy.

Economics is my strongest suit, so most of my posts have focused on the Indian economy — although I have done some posts on other “hot” culture wars as well. With so many flawed ideas floating around in our national discourse, this blog is a humble1 attempt to push back and offer a more grounded, alternative view.

If you’ve enjoyed reading my posts or found them thought-provoking, I’d be grateful if you shared them—on Substack, social media, or word of mouth. And if you run your own Substack, a recommendation would go a long way in helping this work reach others.

In the last Industrial Policy (IP) post, I talked about the necessity of IP and some high level recommendations. You can find it here:

In this post, I intend to talk more about how China uses trade and its effect on industrial policy. Also, the RBI plays a crucial role in IP. This is going to be one of my theory-heavy posts. Specifically, what can be learned from the financial and trade strategies that China employed? Each country forges a different path to industrialization. The West in the 19th century, East Asia in the 20th, and China in the late 20th and early 21st — each experienced a rise, but none followed the same path. But there are common principles that emerge from these experiences. Let’s see why these must be picked up by India.

Addressing arguments against IP

Before we get started, let’s address some critiques of IP. My last post got a good response and there were some common criticisms that I want to take some time and address.

1. Factor market reforms are more important than IP

This is by far the most common response. Factor markets are where businesses purchase the resources they need to produce goods and services. Common factors of production are land, labor and capital2. To be fair, markets for all of these factors are often distorted, have archaic regulations and frequently consist of entrenched interests that prevent reforms. For an example of how land and labor markets are distorted, check out my posts on agriculture and labor laws:

However, reforming factor markets takes a long time. There are vested interests that need to be overcome. To score political brownie points, opposition politicians will try and paint the government as anti-poor. In the case of land, reforms come under the jurisdiction of the states so they’ve to be the ones to initiate it.

Because such reforms affect vast swathes of society, they’re taken up and implemented slowly. What do you do in the meanwhile? You can still choose policy instruments that allow you to compensate companies for the higher cost of doing business in these inefficient factor markets. And that’s what India’s IP is doing.

2. IP involves central planning which is often a failure

I’m no central planner. I firmly believe in the power of markets in allocating resources. And I freely concede that central planning is a pitfall — an all-consuming black hole of money. Having said that, IP doesn’t necessarily mean that going all in on central planning. And using it for run-of-the-mill low-tech industries doesn’t make sense.

How do you start a semiconductor fab? What happens when you want to indigenize defence production? All of these are related to national security issues. Such sectors produce positive externalities for the country, but because these positive externalities can’t be captured by firms, the market fails to produce the socially optimal amount of these goods. Of course, the pitfall with this logic is that firms will lobby heavily to have their sector be one of “national interest”.

In India’s case, millions of people join the workforce every year. Additionally, we would like to shift the economy more into manufacturing from agriculture. Therefore this requires generating more jobs to absorb those who would like to leave agriculture and join higher earning sectors. Central planning in a few strategic, targeted sectors does make sense.

And almost every country in the world has resorted to IP. The US has the CHIPS act. Even Chile’s famed free market economy used IP liberally. Not resorting to IP is effectively choosing an IP to de-industrialize the nation.

3. IP can’t work without good state capacity

Out of all the criticisms, this one is the most valid. IP needs robust state capacity to be successful.

Highly technical bureaucrats are needed to design rules and evaluate companies’ submissions. Without stringent rules, an ability to enforce them and a certain aloofness of bureaucrats from industry, it is easy for IP to devolve into crony capitalism.

In the Indian situation, low state capacity and complex rules were partially responsible for the failure of PLI. I’ll say this though: many schemes and reforms have to go on in parallel. Both are processes involving continuous improvement, and waiting for one to complete will just squander away the demographic dividend.

4. ‘X’ Reform is more important than IP

The final flavor of criticism is that ‘X’ reform is more important than IP at this stage in our development. Add your favourite ‘X’. The most popular usually are:

Judicial reforms

Tax reforms

Education reforms — which translates to increasing human capital

And here’s the thing. These people are right — depending on what their definition of IP is!

I have three points to make here:

At its core, IP isn’t a free lunch. You’re pushing resources into certain sectors and telling people to push up supply there. From this, it follows that resources are being taken from somewhere and production is being pushed down. IP is merely a way to transform the structure of the economy. India is a big economy and you can transform the structure while simultaneously pursuing reforms.

It also depends on what IP is being implemented. If IP is targeted subsidy to companies in a certain sector, then it does make sense to focus on other more important reforms while using IP as a stopgap measure. But if it is something like Special Economic Zones (SEZ), then that essentially allows you to leapfrog all these reforms by creating an area where the usual laws impeding growth don’t apply.

It is imperative to look at IP from a perspective of national security, rather than national wealth. Central planning while inefficient, is a way to indigenize crucial technologies of the future. It is a cost we as a society pay as part of our defence. Falling behind in these technologies isn’t an option, especially considering the geopolitical environment that India is a part of.

Using Trade as an Instrument for deindustrializing

With the arguments for and against IP out of the way, let’s examine the role central banks can play in the industrialization of a country. Because this is going to be theory heavy, I’ll try to include a lot of explainer links. If there’s something that’s difficult to follow, I’d be happy to clarify in a comment.

Do we want to let China and other industrialized nations dictate India’s Industrial policy? The World Trade Organization (WTO) and General Agreement on Trade and Tariffs (GATT) have worked hard to break down trade barriers across the world. In the process, they’ve created a hyper-networked and hyper-globalized world. In today’s world, a country can effectively imprint its industrial policy onto its partners’ trade policy—and vice versa—blurring the line between domestic strategy and international consequence.

China’s trade policy has often defined our industrial policy. How? With excess domestic production capabilities, the price of a manufactured good quickly falls below its production cost, unless it is able to export that capacity. When it exports that capacity, it reduces the competitiveness of those sectors in the partner country where the goods land.

Let’s take a concrete example. There’s a trade deficit between China and India. Depending on what data source you choose — I chose the Organization of Economic Complexity — it is about $105 billion. The two images below visualize the trade deficit between the two countries.

With China’s production capacity, it is able to cheaply export goods and India’s manufacturing sector is unable to expand to the extent it could have, had the overcapacity not been present. In fact, if China is able to outcompete local manufacturers on price, it can forcibly de-industrialize India, which is what has actually been happening. So China’s industrial policy influenced our own industry without India having an active industrial policy.

In fact, let’s generalize this to the whole world. Countries with trade surpluses are exporting manufactured goods, which they’re only able to do because manufacturing is promoted by the industrial policies there. Such policies attract global manufacturing powerhouses to manufacture inside those countries’ borders. India, by virtue of not having any industrial policy has an industrial policy that favors services! Why? Because manufacturing isn’t being given as much of a concerted push, it is uncompetitive to produce goods in India and cheaper to produce services. And that’s exactly how the economy is structured currently. Services are a much bigger part of the economy.

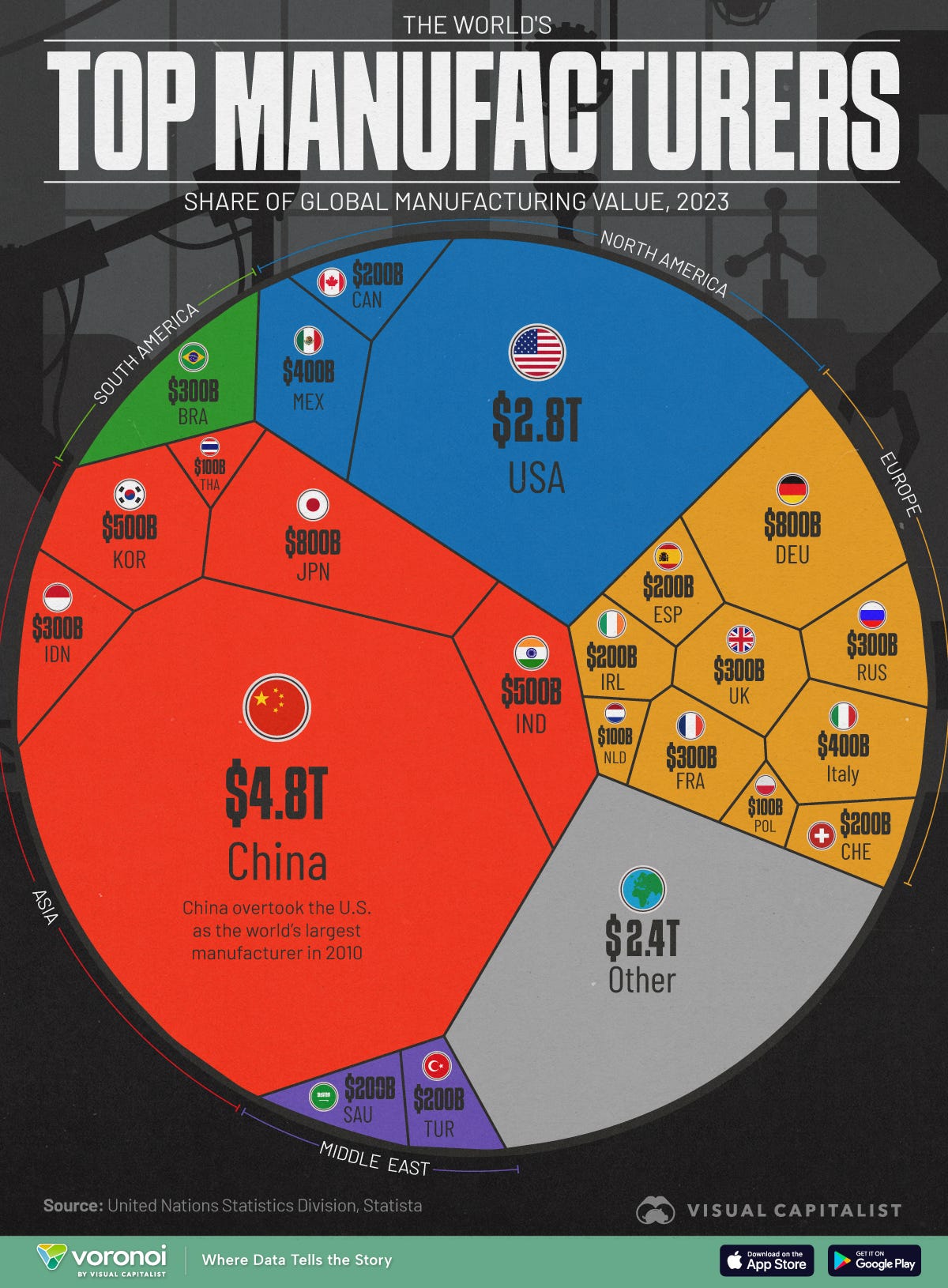

Another reason why India must have Industrial Policy: In a global world, manufacturers are now able to export to any location on the back of the globe. If China, Singapore, Korea or Taiwan are subsidizing manufacturers the most, manufacturers will naturally gravitate towards these countries. And the data bear that out, manufacturing comprises almost 30% of the above economies’ GDP.

A note on Finance as Industrial Policy

It might be surprising that India’s RBI runs its own “Industrial Policy”. It does this by keeping the rupee overvalued. For a few years now, the RBI has tried to defend the rupee by trying to keep it within a narrow band. Needless to say, it has failed. Forex markets are vast, and trying to battle them is a losing endeavour. Precious dollar reserves are spent only to slow down the rupee’s slide to its natural level.

The Real Effective Exchange Rate (REER) is a measure showing the strength of a country’s currency compared to a weighted average of its trading partners’ currencies. It compares the value to a basket of currencies and adjusts for inflation differences. It is crucial to understand a country’s trade competitiveness. If the REER rises, it means that the currency is appreciating and its exports become more expensive, and the export sector loses it competitiveness.

According to the REER, the rupee is overvalued by about 10%. Keeping the rupee overvalued hurts exports which become more expensive in dollar terms compared to other undervalued currencies like the Chinese Renminbi. Industrial Policy must be thought of as holistically. While offering strategic support to each sector might be infeasible, the first step towards a good industrial policy is to have a fairly valued rupee rather than an overvalued one. Slight undervaluation works wonders for exports.

Again, there are no free lunches though. In effect, an undervalued currency would be akin to a subsidy for exporters while penalizing consumers because imports become relatively more expensive.

This was a relatively short, but theory dense post. I would like to hear your thoughts on these types of essays, so please free to leave a comment and let me know. Next time, I plan on examining how different nations are shaping up their semiconductor policies to capture this emerging strategic industry.

Some might call it an arrogant attempt.

Entrepreneurship is a also considered the fourth factor of production because entrepreneurs are the ones who unite the three factors of production to actually produce goods or services. Here I’m ignoring it in favour of simplicity.

Why does India’s central bank want its currency overvalued?