Only Capitalism Can Annihilate Caste

Free markets are a powerful weapon against caste—if anti-caste activists are willing to use them.

Before we get started on this juicy and contentious topic, I want to get some terminology out of the way. That way, when I get attacked for my position1, we aren’t quibbling over nomenclature.

The term ‘casta’ — from which the word caste comes about — was first used by the Portuguese. Duarte Barbosa first used it in a text to describe groups he encountered on the Malabar coast. For Barbosa, caste combined endogamy and occupational practice. It is likely that use of the word ‘casta’ spread throughout the world through the global networks of Jesuit missionaries2. Regardless of what they understood caste, the Portuguese certainly did not differentiate between jati and varna. Varna is the fourfold division of labor mentioned in the Purusha Sukta3 of the Rig Veda. Jati refers to the occupational roles or tribal associations and it could be mapped onto one of the four varnas. The division between varna and jati is horizontal rather than vertical. A jati could be mapped onto a different varna in different places.4

Capitalism refers to free markets with minimal government regulations5. There’s often a false dichotomy that’s presented between capitalism and socialism. An economy is always somewhere between the two extremes. Pure capitalism is indistinguishable from anarchy and pure socialism is indistinguishable from communism. In the Indian context, a capitalistic approach would take the form of a hands-off approach to the economy. The Indian economy is over regulated, with the Indian State having its proverbial hands in everything from labor to agriculture to oil and much more.

Previously, we have covered the distorting effect of government regulations on agriculture, how India’s labor laws are needlessly convoluted and what the absence of a plan for deregulation in the 2025 Budget. Although the 1991 reforms opened up the Indian economy, dismantling of the license raj was only a starting point. For India to develop a true free market, reforms should have continued. What does it say about our pre-1991 economy that even after the much-vaunted liberalisation, privatisation and globalisation, the Indian economy — more than 30 years later — still overregulates markets6.

Annihilating caste means different things to different people. In this essay, I define it as diminishing the significance of the jati-varna complex in society7.

Why do caste identities arise?

The rise of caste is a complex topic and numerous books having been written on it8. The widespread view is that varna was mandated by the Rig Veda and used by Brahmins to cement their control and power over the indigenous population. Depending on occupation, the different jatis were mapped onto the varna system. The higher up in the varna system you went, the better your social standing.

There are some gaps in the theory above, but I’ll highlight just one for brevity. How did Brahmins sustain their social dominance without political power or financial muscle, which were typically held by the Vaishyas or Kshatriyas? It seems implausible that such a system persisted without resistance or rebellion. Additionally, the classification of certain jatis varies across regions—some are categorized as OBC (Other Backward Classes) in one part of the country while being considered upper caste in another. This suggests that the system allowed for some degree of social mobility over time.

Nicholas Dirks, in “Castes of Mind”9, traces the origins of the jati known as the palayakarars. Early Tamil literature depicted them as thieves, a label later reinforced by the British under the Criminal Tribes Act. However, the Kallars, a subgroup of the palayakarars, had well-organized social systems rooted in kinship and territorial ties. This allowed them to offer formal protection to other communities, gradually elevating themselves to the status of local chieftains. The Kallars rose to power as the rulers of Pudukkottai, aligning themselves with the British East India Company against other palayakarar subgroups. This alliance likely played a crucial role in Pudukkottai remaining the only princely state retained in Tamil Nadu. Interestingly, the Kallars in other parts of South India often found themselves outside the rigid confines of the varna system. Their place in the social order seemed to rise and fall, not by divine decree, but by the ebb and flow of political fortunes. In other words, who you sided with often mattered more than where you were slotted in the traditional hierarchy. This wasn’t some grand act of rebellion—it was simply the reality of power politics.

I can already hear the counter-argument—what about the Brahmins, the eternal gatekeepers of ritual and tradition? While the Brahmins were indexed at the top during rituals, when it came to temple honors, the pecking order told a different story. Temple honors were given first to the king and later to the Brahmin. The Kallars were respectful of Brahmins but were very clear that they depended neither on the Brahmins nor on Brahminic influence to maintain their position. Their powers came from their access to land, their political influence and strategy, not from sacred texts or priestly blessings.10

Why spend so much time on the history of a relatively small caste in southern India? Because their story reveals a fundamental truth: the caste system in the early 18th century was far more fluid than we often assume. The same caste could hold elite status in one region while being marginalized in another—clear proof that land ownership was a key player in shaping social hierarchy.

Land has always been a marker of wealth, but in earlier times, it was absolutely essential for anyone with political ambitions. If feudal politics could overturn caste hierarchies, why wouldn’t wealth in the modern economy do the same? And while the world has changed, one thing remains the same—access to wealth can still flip political fortunes, just as it did centuries ago.

How do you get access to wealth? Embracing free markets and deregulation allows businesses to prosper. Once wealth is accumulated, the caste system loses its grip on social interactions. Economic mobility reshapes traditional barriers — when financial success levels the playing field, social divisions rooted in caste become far less rigid.11

Prejudice is Free, But Discrimination Has Costs

Contrary to popular belief, the government isn’t the only entity standing in the way of discrimination in the private sector12. True, the government can make it harder to discriminate on the basis of caste, but the real incentive to not do so comes from free markets.

Economic theory predicts that discriminating against employees on any basis other than productivity will lead to a penalty imposed on profits. If a firm isn’t able to make enough profit relative to its costs, it will soon be outcompeted by other firms, forcing it to change its methods or go out of business.

How does this work in practice? If male and female bakers are equally productive, but sexist bakery owners prefer men, demand for male workers will drive up their wages. Higher costs mean lower profits unless customers pay extra for a bread baked by a male. Profit-focused owners will ditch bias, hire women, cut costs, and boost profits. Even if all refuse, women-owned businesses can undercut them on price by hiring only women. Unless the government shields the bigots, competition will force firms to choose: hire women or lose money. Over time, this raises demand—and wages—for female workers, making discrimination an expensive habit that fades away.

Great Theory, What is the Practice?

Just because economic theory predicts something about the real world, doesn’t mean that it actually happens that way. The theory of discrimination, while compelling, isn’t worth much unless we say it play out that way in the real world. Are there any examples that would test this theory? As it turns out, there are plenty! There are two particularly illustrative ones that I’ll lay out.

Apartheid South Africa

Apartheid South Africa had government imposed penalties on hiring Black workers. Business owners, mostly White, were forced by law to hire only White workers for higher paying jobs. White workers were able to successfully lobby for extreme restrictions on black workers’ ability to work. Between 1893-1918, gold mining unions restricted the employment of non-whites. The price of gold being set internationally, mines had to produce gold at the lowest cost possible otherwise they would be uncompetitive internationally and consequently domestically, because people would simply import gold from international markets.13

Mine owners illegally hired non-whites in an effort to evade government mandates on hiring Whites. The situation was so dire for the mines, that the owners laid off a third of their White workers replacing them with blacks. The wages of other white workers could also be reduced, because there was a greater supply of workers. There were violent labour protests against this and the matter went to court. Luckily, the courts ruled that the government didn’t have the authority to set up racial quotas. In 1924, mines reported their highest ever profits till then.

Racial Segregation in the United States

Many states and municipalities in the American South had segregation laws in the 1950s. Among those opposing this vociferously, were privately owned railroad and streetcar companies. The opposition wasn’t out of a sense of social justice, it was pure economic interests at play. Segregation meant having separate streetcars and railcars for Whites and Blacks. In effect, railroad managers had to run two half-full cars instead of just one full car. Obviously, profits decreased and business owners complained. In some areas, streetcar companies refused to enforce segregation laws for almost 15 years after their passage. Unfortunately, the case went to the Supreme Court where the court said that “separate but equal” laws were constitutional. In an ironic twist, the companies were accused of “putting profits ahead of the welfare of the region”14. Where have I heard this before?

Another example is provided by Thomas Sowell, from the antebellum South where white workers complained that black workers were undercutting them with their wages. Sometimes, white workers even got legal restrictions against blacks, preventing their wages from falling.

A Hypothetical Scenario

Let’s do a thought experiment. Suppose there were no restrictions on genetically engineered (GE) crops, and everyone was free to grow them. GE crops have better yields than conventional crops, primarily because they can be designed to be resistant to common pests15. When yields go up, less land is required to produce the same crop, so there could be a possibility of land costs going down. Who benefits from land costs dropping? The most marginalized caste groups in current society, some of whom would now be able to own land.

This experiment might not play out exactly in the real world, because various other factors come into play, but the basic idea holds. Free enterprise is a powerful tool and economic interests end up having secondary beneficial effects. Each person acting in their own economic interests, produces outcomes that they didn’t have in mind.16

What does the data say?

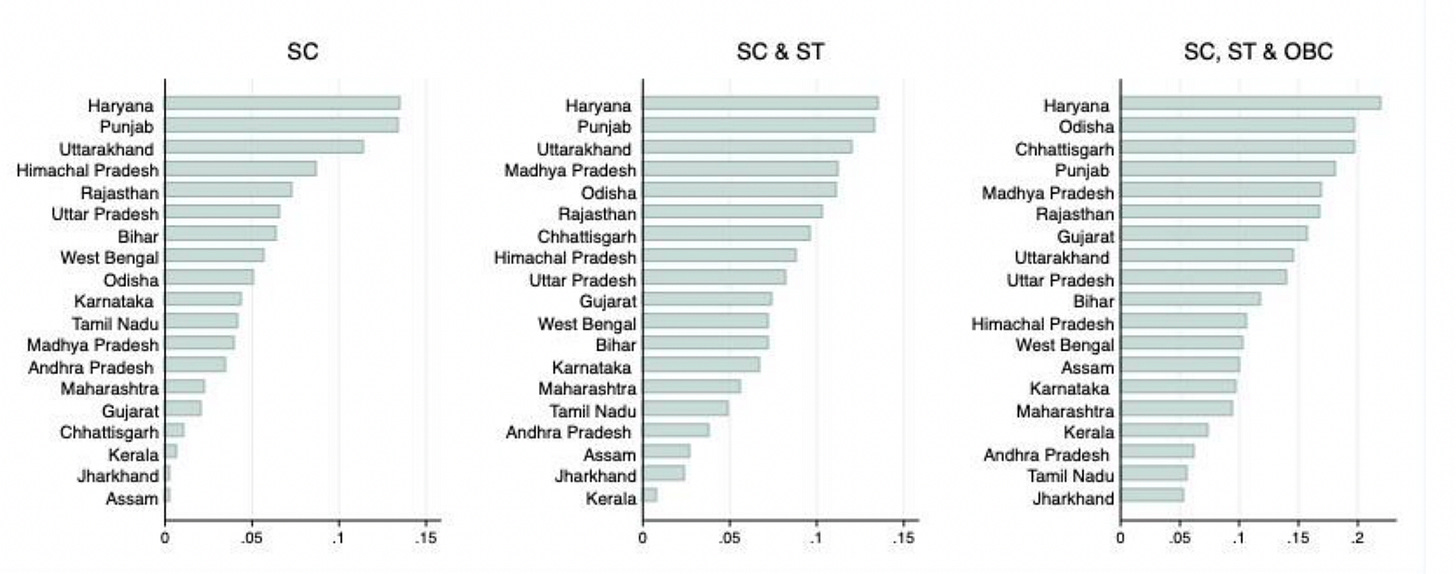

It is hard to find data in India comparing caste discrimination across states. The best proxy measure I could find was the level of income inequality across states. The India Human Development Survey (IHDS) is a nationally representative survey that collects data on caste. Poulomi Chakrabarti has constructed the following graphs helpfully in her paper on caste inequality across Indian states.

She constructs a Between-Group Inequality (BGI) index which measures inequality between groups. BGI ranges from 0 to 1 and the larger the BGI, the higher the correlation between caste and income. The above graph shows that Gujarat has one of the highest BGI indices, followed closely by Maharashtra. Tamil Nadu has very low BGI too, along with Andhra Pradesh17.

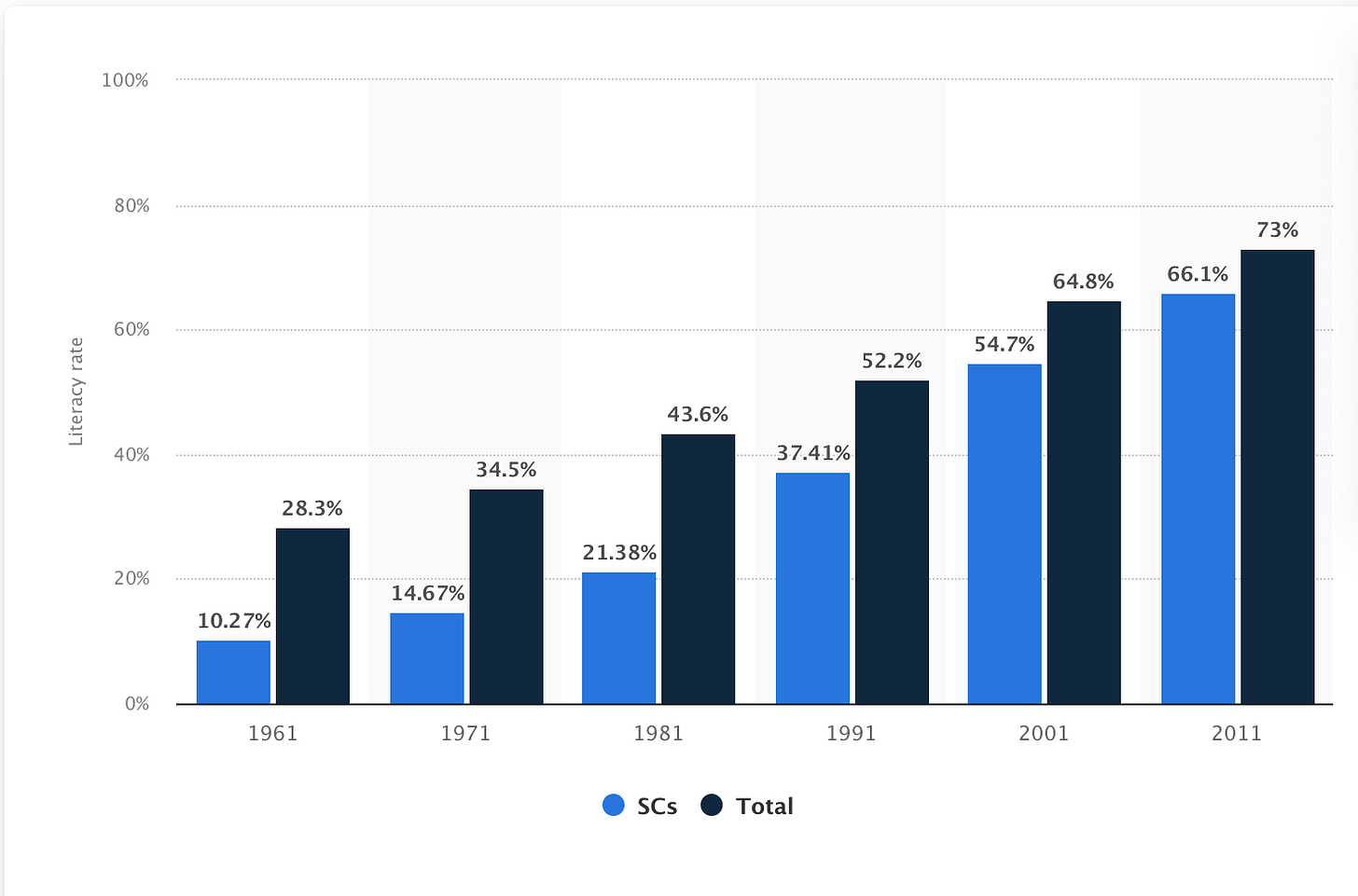

Another proxy measure that I think is informative is Scheduled Castes (SC) relative literacy rates to the general population. Looking at the above graph, 1991 is the inflection point where the economy loosened and allowed private businesses to thrive. In 1991, there’s a 15 percentage point gap between SC literacy rate and the general population literacy rate. This gap comes down to 7 percentage points by 2011. It has been 15 years since the last census and it is highly likely that the gap would have narrowed even further. Literacy rate has a lot of confounding variables, but unless there’s economic benefit to be had, the bottom strata of Indian society chooses to keep their kids home rather than send them to school18.

As the pandemic had a disproportionate impact on the poorest segment of society, many families chose to have their kids help out at work rather than invest in school, where economic returns are uncertain. I presume that this would present a starker choice to marginalized groups too.

I don’t want to give the impression that government regulations are ineffective19 — only that their scope must be carefully considered. In a polity like India, where the instinct is too overregulate as if we are a $40,000 Per capita income economy, it is better to err on the side of light regulation and foster a high-trust society.

Because there does exist evidence of caste discrimination in workplace situations, it might be unreasonable to expect free markets to truly drive out discrimination. If discrimination is happening upstream of the job interview process, such that people belonging to marginalized castes aren’t getting credentialed, no amount of deregulation would be able to get rid of it. Only in such situations is it appropriate policy for the government to pass regulations.

Inevitably, I might add?

This is Angela Barreto Xavier’s argument in her essay titled ‘Languages of Difference in Portuguese Empire’. She talks about how the `casta` label spread across the world and what the Portuguese had in mind when they referred to `casta`. Did they only refer to jati or were they aware of varna?

Koenraad Elst has an excellent article on the nuances of the Purusha Sukta.

The Kolis are the perfect examples. They’re classified as OBCs in Gujarat, Maharashtra and Karnataka. In Delhi, Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan, they’re classified as SCs. Within the Koli community, Mahadeo Koli is recognized as a Scheduled Tribe (ST) in Maharashtra. Mapping this onto the varna system, this implies that Kolis were avarna in the northern parts of the country, but were savarna in other parts.

Capitalism is an extension of classical liberalism in the economic sphere. One of the pillars of liberalism is the right to own private property. The origins of capitalism lie in being allowed to own private property. The other pillar of liberalism is individual freedom and autonomy. How do you have any freedom if there’s no autonomy to do as you see fit with private property?

I’m not arguing for unbridled capitalism — some regulations are essential to curb monopolistic and oligopolistic tendencies. However, does the Indian state limit its control to just preventing such market distortions? No, it often intervenes preemptively, driven more by anticipated fears than by actual market failures. The recent farm laws are a case in point. Unfounded fears of corporates running roughshod over farmers contributed to turning public opinion against it.

Completely dismantling the caste system is a complex and challenging task. Throughout history, many societies have had rigid social hierarchies resembling caste. Japan had the shinōkōshō system, Korea had the baekjeong (historically marginalized groups), Imperial China maintained a structured division of labor, and even pre-colonial African societies had caste-like distinctions. While these formal caste systems have been officially abolished, social divisions persist in different forms, often manifesting as class distinctions. This raises the question: Are these evolving structures simply old hierarchies repackaged in new forms?

A good book to start with is “Castes of Mind” by Nicholas Dirks. Its main thesis is that caste as we know it now, was how the British understood it and they managed to impose it on the populace through state machinery. It doesn’t mean that caste didn’t exist earlier, but it acquired new salience in the British era. I’ll probably do a future post on a reading list related to caste.

Chapter 4, Castes of Mind, Nicholas Dirks, p. 66.

Drawn from Nicholas Dirks’ monograph, The Hollow Crown: Ethnohistory of an Indian Kingdom.

Another counter-argument possible here is that because caste signifies social standing, it wouldn’t be erased with access to wealth. That’s precisely why I brought up the Kallars example. It is an example of a caste moving up to royalty while being outside the caste system in other parts of the country.

The title of this section, “Prejudice is Free, Discrimination Has Costs” is the title of a famous paper by Steven Farron where he expounds on this principle provided by Thomas Sowell, another famous US based economist.

In this case, another intervention by the government to preserve segregation could be to impose heavy import tariffs on gold to allow unproductive mining companies to continue operations.

Edward L. Ayers, The Promise of the New South: Life after Reconstruction (New York: Oxford University Press, 1992), p. 143, 144, 433.

I realize that this is controversial, but most of the evidence I have surveyed points to GMO crops being absolutely safe to consume, while being economical to grow. I covered this in some of my earlier posts on agriculture, but I’ll flesh out this concept properly in a future essay,

This is what Adam Smith refers to, when he says, the “invisible hand of the markets”.

This survey was conducted in 2010-2011 so it is referring to united Andhra Pradesh.

I’m probably guilty of over generalization here, but my core point still holds. See this article for more on challenges of poverty faced by Indian kids.

But they mostly are!

To describe it in todays vocabulary, isms, caste, jati, varna, professional title, all relate to a timeline -related identity of peoples work at different times of many different govts/kings/colonisers/religious converters/ religious movements…. But… but when communities titles which were identities of families (the foundations of civilian communities… as in children’s identity)became weaponised for political conquest the ideas morphed into toxic demarcations for divide& rule to deprive means for earning, gain power(race, caste, jathi, etc…), create generational lack in industrial age over an agricultural times by propaganda of hierarchy, where the idea of the other as subaltern was popularised for economic& social deprivation. People deprived of means to find work to feed family rarely had time to understand statecraft in new language models of govt., the laws that unfairly just labeled people into prisons for speaking up. It took years upto 47 to rewrite a possible system to help communities find means to live. The archives hold many detailed statecraft documents that speak of how to rule over the subcontinent to take wealth& control local communities. The unfortunate aftermath of the propaganda is found to this day as contentious politics due to poverty, economic deprivation issues where caste, class, jathi reservation …all had lack of possibility to get work to feed family& community… these required new age learning & often spoken of language challenges that cause social divisions mistaken for caste issues. Not very different from some urban calling a religious majority/minority poorly concocted labels- the need to divide … the idea of the other. It’s the weaponised toxic bias of divide& rule syndrome.

The Annihilation of Caste by Adam Smith