I

Donald Trump dubbed April 2nd as “Liberation Day”. The Trump administration put tariffs on every country — including one that has no inhabitants other than penguins. They even tariffed one of their own military bases1. Stocks and bonds went off the precipice and took a big tumble. It is likely that the global economy will head towards a recession.

Let’s take a minute to go through the ridiculousness of this exercise. The Trump administrations formula for computing tariffs is dividing the trade deficit by the imports from that country. I wish English was my native language so that I could find a word for this breathtaking stupidity — sorry for the invective2. This formula hit small impoverished nations — exporting a single commodity to the US — with significant tariffs. How can a third world nation, exporting coffee beans or diamonds to the US, buy fancy US-made cars?

Economists have been unanimous about the deleterious effects of tariffs. Tariffs are a form of tax paid by consumers. Unless prices rise, tariffs will not be effective in moving manufacturing back to the US3. And Trump has threatened auto manufacturers to keep prices low — the implication being that he’ll hit them with regulation otherwise. This is a classic case of a price cap and everyone knows how that turns out4.

Infinite Scroll has a good example of the ludicrousness5 of these tariffs:

He is, sincerely, just a very stupid guy who thinks that when we buy vanilla beans from Madagascar - which grows 80% of the world’s vanilla supply - they are by definition ‘ripping us off’. It’s only ‘fair’ if they buy back an equivalent amount of Boeing jets, which they can’t do because they’re a desperately poor third-world country. This is a moronic thing to believe, much in the same way that it would be moronic if I said my barber is cheating me because I buy haircuts from him but he doesn’t buy blog posts in return from me. It would be stupid to cry about my ‘trade deficit’ with my barber. But Trump sincerely believes it. He does not have complicated theories about Bretton Woods or monetary theory or the international trade system rebalancing. He simply thinks trade deficit = cheating, by default. That’s why poor little Madagascar has been hit with a new 47% tariff rate.

All of this pain is going to end up hurting Trump’s core voter base. Affluent voters are more likely to vote Democrat. Midterm elections are up in November 2026. I don’t see how Republicans survive the bloodbath likely to occur.

II

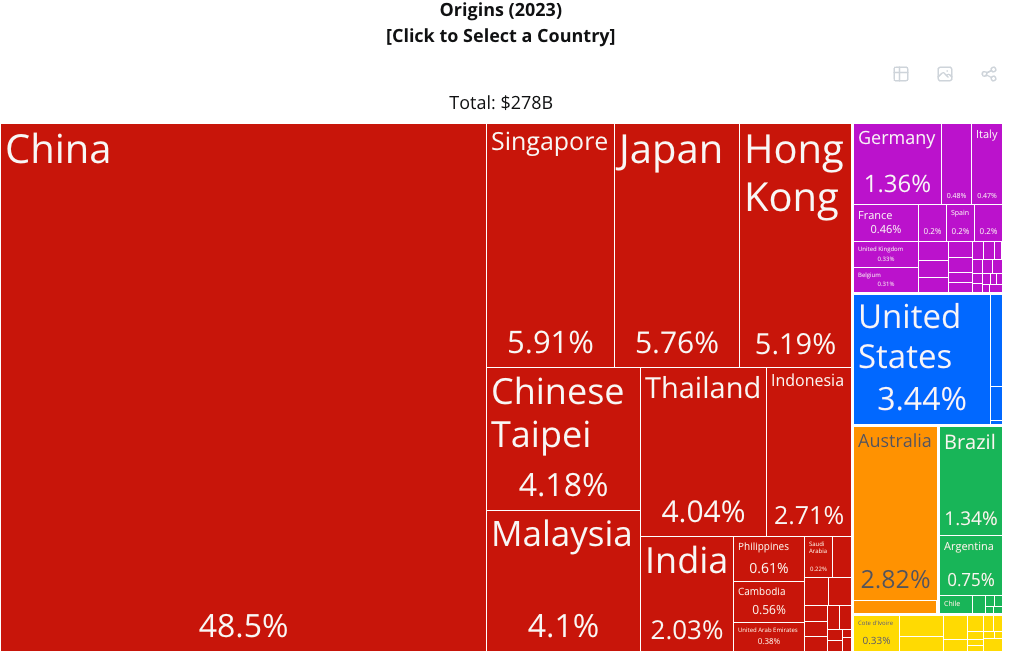

When looking at the effect of tariffs on India, the first thing I look at it is India’s trade and exports. Here’s a graph of India’s exports in 2023.

And here’s what it exported to the US in 2023.

Looking at India’s exports, there’s a good balance of manufactured goods and raw materials. It isn’t too dependent on mining raw materials and selling them off. That’s a good sign for a country trying to become rich and developed. The only worry is that none of India’s exports are too labor intensive.

About 20% of India’s total exports are to the US. The good news is that Trump’s tariff order excludes pharmaceuticals, petroleum products and semiconductors are exempt from tariffs — for now. That’s around $15B of products that wouldn’t be tariffed. India has been hit with a 26% tariff rate by Trump. Other countries are faring worse with China facing 54%, Vietnam facing 46% and Bangladesh subjected to 37% tariffs.

China was already facing a 20% existing tariff rate and now it’s been increased even more. Because of this tariff rate, China made investments in many other countries to increase their manufacturing capabilities. With its factories in these countries, it could then route its goods to the US without it having to pay the steep tariffs.

Vietnam’s FDI from China increased by 33% in 2023 and it received the majority of its raw materials from China. The US was Vietnam’s single biggest export market.

This was an attempt — a pretty successful one — by China to evade US restrictions on imports from the country. Vietnam benefited from the investment and it was a win-win all around. China used the same playbook with Mexico. Mexico, Canada and the US signed a free trade agreement — known as the USMCA — which allowed free trade of goods in North America. Taking advantage of that, China invested a lot of FDI in Mexico, hiding much of it, and then using it to export goods to the US. In 2023, Mexico surpassed China as the United States’ largest source of goods.

III

According to Joe Studwell’s How Asia Works, the the path to a developed nation usually consists of just export led growth. Services can be part of the export mix as well, but the main reason that exports work is by exposing different sectors of the economy to international competition and best practices. The process elevates firms’ productivity and has various spillover effects on other parts of the economy6.

Exports should be more than just raw materials. Finished goods are typically more expensive, have associated intellectual property and are immune to commodity cycles. Finished goods also tend to be more labor intensive creating much needed jobs in developing countries.

Bangladesh has been hit with 37% tariffs and its single export to the US is its textiles industry. The country also benefits from Least Developed Country (LDC) status that offers it zero tariffs in many markets. Textiles are labor intensive and have the potential to create tons of jobs. I suspect that this industry is one of the reasons why Bangladesh is more urbanized than India.

India is well suited to capture the business exiting Bangladesh. It is already the third largest textile exporter. Bangladesh benefited from the LDC status and provided export subsidies to its industry. On the other hand, India was burdened by archaic labor laws and high tariff on raw materials for textiles7. Because Bangladeshi companies enjoy companies of scale, they have faster turnaround times on product and are able to get a consignment to a port within a day. India performs worse on both measures.

On the surface, it appears that the Indian textile industry suffers a host of problems. However, it is just a couple of upstream issues that cause distortions downstream. Textiles require two main inputs: good ports to transport apparel to global markets, flexible labor laws to employ vast amounts of people.

Bangladesh has 9 major ports, while India — 20 times larger in size — has only 13 major ports. For comparison, the US has more than 50 major ports. India’s infrastructure push needs to come online faster.

The second issues is India’s archaic labour laws. Earlier this year, the kaleidoscope of labor laws were condensed into 4 major labor codes. Unfortunately, that’s not much of an improvement qualitatively from the previous smorgasbord of laws. I cover the issues with India’s labor laws in more detail in a previous post.

Briefly put, the new laws still prioritize small scale employers. The definition of small has gone up from 100 employees to 300 employees. But that’s still too small for a textile unit. There are other provisions about minimum wage and pensions among others that make it a rent seeking haven for bureaucrats. That needs to change for India to capitalize on the textiles industry seeking to exit Bangladesh.

IV

Let’s revisit some basic economics and trade theory. Why does Trump want to impose tariffs? Because he wants to bring down the trade deficit? It is likely that he thinks reducing imports will increase GDP.

The formula to calculate GDP is:

GDP = C + I + G + X - M

C - Consumption

I - Investment

G - Government Spending

X - Exports

M - ImportsWith this calculation, it is easy to think that reducing imports will increase GDP since it is the only factor reducing the net GDP amount. What Trump misses though is that imports are also needed to produce exports.

For example, the US exports semiconductors and GPU chips. The raw material needed for most chips is Silicon — in the form of Silica — and a lot of it was imported. Tariffs designed to cut down on such imports will have two effects: either the US pauses semiconductor manufacturing, or it needs to start producing Silica. Both of these are not ideal outcomes. The unemployment ratio is about 4%. There’ll be multiple such changes requiring reallocation of workers to keep exporting what the US currently exports. Does the country have enough workers to support these reconfigurations? If not, then workers from higher value industries will switch to these industries reducing US export competitiveness. Prices will increase to tempt workers to switch. The end goal is making the whole country poorer, including Trump’s core voter base.

However, once a country hits tariffs on other countries, affected countries retaliate with their own tariff barriers. That is not the economically optimal response. For years, the US had far lower tariffs than almost all other countries and yet it was the richest country. Its residents had the highest consumption as a ratio of GDP.

Let’s walk through this with an example. Suppose India retaliates with its own tariffs in response to the US. What does this achieve? It only serves to make India’s already uncompetitive exports, even more pricey. Tariffs will make all imports expensive, even the ones that are used as building blocks to make exports. Consequently, exports also become expensive.

V

It’s easy to give in to rhetoric and slap retaliatory tariffs, but the government mustn’t fall into this trap. As I explained above, tariffs will only make the residents of the country poorer. The other option is to recognize that the US is committing economic seppuku and take advantage of the world economic restructuring that occurs. Since other countries are tariffed at much higher rates than India, it would be criminal to waste the comparative advantage opportunity offered by Trump’s buffoonery.

As I explained, during the US-China trade war, which started in 2018, Chinese manufacturers routed their FDI into Vietnam and Mexico. By manufacturing the final parts in those countries, Chinese exporters were able to indirectly get lower tariff rates.

The same scenario will likely play out this time on. India is receiving record Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) but as a percent of GDP, FDI is barely 1%. Reasons for this are numerous, ranging from a global slowdown in FDI to India’s decision to terminate Bilateral Investment Treaties (BITs) — leaving companies with few options if they need legal protection.

To take advantage of these circumstances, the government must take the following policy decisions:

Reduction in tariff rates. This needn’t be a steep immediate cut in tariffs. That would harm domestic industry. A gradual reduction in import duties would give firms time to prepare for more competition. An added benefit here is that exports become cheaper because their inputs — in the form of imports — are cheaper.

Revamping archaic labor laws. Although they were consolidated in 4 labor codes, the laws are still hostile to business carrying criminal penalties in case of violations. These provide ample opportunities for bureaucrats looking to make a quick buck rent seeking.

Signing more free trade agreements with regional blocks like Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP). India is growing economically, but its participation in global supply chains is waning. Exports are concentrated in those sectors that aren’t labor intensive. A World Bank report lays the claim squarely at the feet of tariffs on key inputs. Participating in these supply chains boosts competitiveness of the firms involved which has spillover effects on the rest of the economy.

VI

How do these reforms get passed though? There’s always special interest groups that oppose any form of free trade. Industry leaders will often try to present their industry as essential to national security to secure protections from international competition. India has a strong farmer lobby that often exercises a street veto on laws inimical to its interests.

One idea was elaborated by Robert Putnam in his seminal paper Diplomacy and Domestic Politics. Essentially, he says that international negotiations are dependent on domestic ratification. Conversely, domestic political compulsions often dictate posturing in international negotiations. This was similar to how India’s Food Security Bill in 2013 led to the US complaining about it to the World Trade Organization (WTO).

India was also pressured to withdraw from the RCEP in 2019. While the south-east Asian nations pressed for massive tariff reductions, industry lobbies threatened nationwide protests. The government was forced to retreat.

Reversing the logic here, the government could show that its hand is forced to reduce tariffs. The probability of a global recession is more than 50% according to Polymarket. Tariff reductions would allow India to escape global volatility relatively unharmed, by allowing growth through FDI and other channels. Because a recession significantly reduces an incumbent’s chance at re-election, the government could play this up a threat, allowing it to carry out reforms at the international level (read tariff reductions) that it otherwise couldn’t have. It could also use this tactic to generate political capital to push through domestic reforms.

There’s been ton of ink spilt on what exact reforms India needs. Everyone pretty much agrees on the basic set of reforms needed. There are countless laws that provide rent seeking opportunities to bureaucrats — empowering them to harass businesses. Sanjeev Sanyal — in the PM’s Economic Advisory Council (EAC) — himself says that he lost the battle to defang Legal Metrology laws — one of the main tools used to harass businesses. Until these laws go, there cannot be a business friendly environment. Cosmetic changes help to a degree but until fundamental reforms are carried out, it’s akin to putting lipstick on a pig.

The main question remains: Does PM Modi have the political will to execute them?

I don’t even know how this happens. This Trump administration is really a kakistocracy.

In this newsletter, I usually try to maintain a neutral tone especially concerning politics. But I think the situation justifies an exception to my rule.

The first question here is why should manufacturing move to the US? The US produces far more value up in the supply chain. Why not focus on that part? There are good arguments to maintain a manufacturing base in the interests of national security in industries like defence or semiconductors. But there’s no economic justification for bringing back all of manufacturing, unless America just likes being poor.

Refer to my post on agricultural price caps for a brief overview.

I have a thesaurus trying find synonyms for “stupid”. This word is going to be used a lot in the essay and unless I find synonyms, it will get repetitive.

Noahpinion has a great series on the industrialization of developing countries where he applies Studwell’s lens.

Ironic, isn’t it? Another data point for how tariffs almost always end up hurting.

I like this a lot because it argues for reforms that are just good, with or without Trump tariffs.

I'm glad it's not one of those pieces arguing for some specific benefit from a particular policy in another country (US tariffs, in this case). Those never work because: i) the policy environment can change rapidly (100x more volatile given Trump), ii) it's pointless to expect that govt can pick the right sectors & winners, etc.; it's a recipe for cronyism.

Wise predictions

Great researcher write up 👍🏻